Davis Vernon Kruse was born in the small town of Little Rock, Iowa, on 29 January 1919. He was the eighth child of Kreen and Dorothea (or Dorothy) Stroh Kruse, and spent his early life on their farm in Lyon County. When Vernon (as he was known) was very young, the family relocated to Worthington, Minnesota. Unfortunately, Kreen and Dorothy’s marriage did not last long after the move, and by 1930 they had separated. Mother and children moved to Lismore, where Dorothy took over management of a local restaurant. The older boys worked on local farms, while the girls waited tables and the younger kids went to school.[1]

Davis Vernon Kruse was born in the small town of Little Rock, Iowa, on 29 January 1919. He was the eighth child of Kreen and Dorothea (or Dorothy) Stroh Kruse, and spent his early life on their farm in Lyon County. When Vernon (as he was known) was very young, the family relocated to Worthington, Minnesota. Unfortunately, Kreen and Dorothy’s marriage did not last long after the move, and by 1930 they had separated. Mother and children moved to Lismore, where Dorothy took over management of a local restaurant. The older boys worked on local farms, while the girls waited tables and the younger kids went to school.[1]

Vernon finished grade school before returning to Iowa; part of the family moved to Waterloo. By 1936, he was done with grammar school and began attending East High School, but left in order to find work.[2] Permanent jobs were not easy to come by; Vernon was employed off and on as a laborer, and even spent three months learning forestry with the Civilian Conservation Corps. His most steady work came from the Central Illinois Railroad, but even that could be sporadic and Vernon occasionally had to list himself as “unemployed.” When he wasn’t working, he may have joined in some pick-up baseball games – a sport he enjoyed in school – and frequently went out hunting with rifle and shotgun.

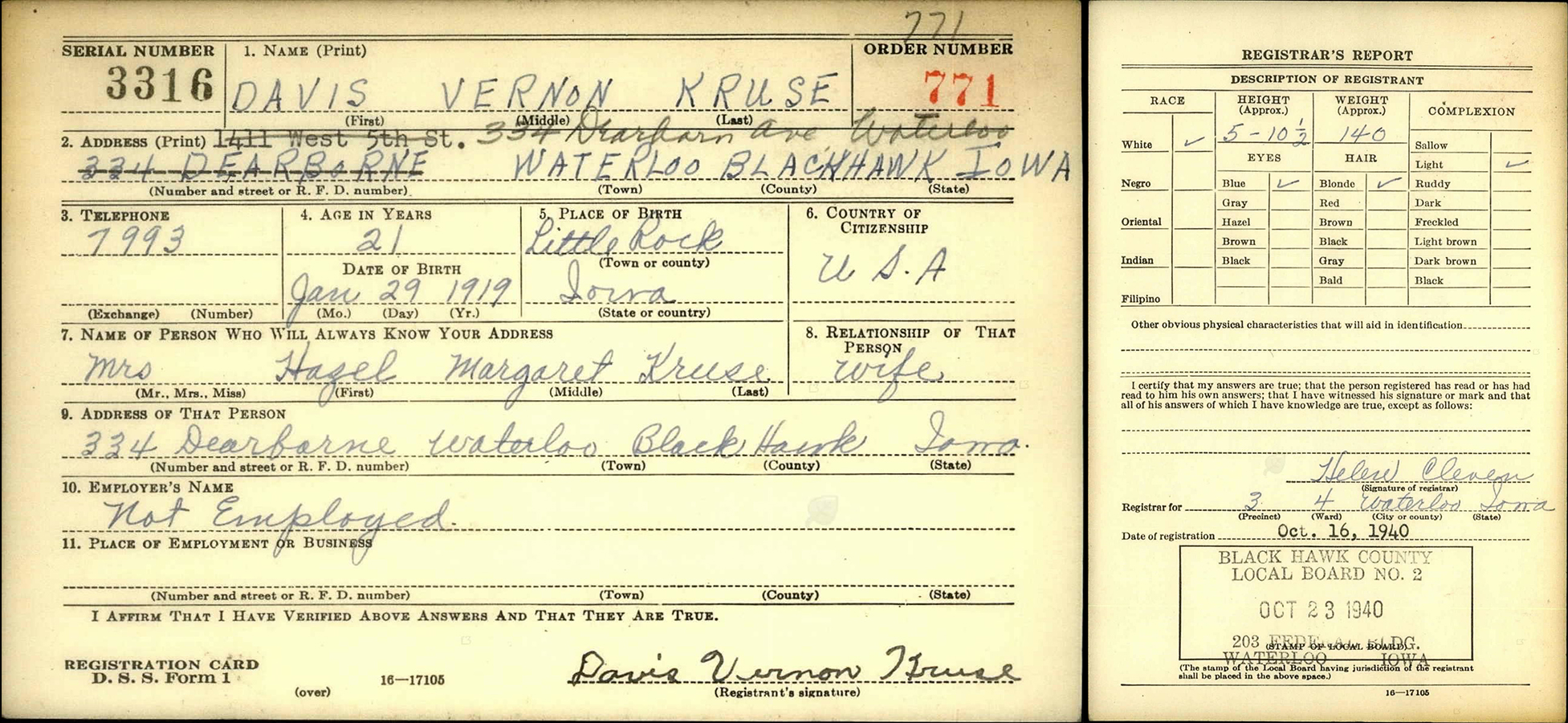

The year 1940 was a big one for Vernon Kruse. On the sixteenth of January, Kreen Kruse died in his sleep, the victim of a probable epileptic seizure. A few days after the funeral, Vernon observed his twenty-first birthday – and a few days after that, celebrated his marriage to Miss Hazel Margaret Cutler. The newlyweds settled in with the Cutlers on Dearborn Avenue (a temporary solution, they hoped) and Vernon continued working his odd jobs. Finally, in October, he registered for Selective Service.

The year 1940 was a big one for Vernon Kruse. On the sixteenth of January, Kreen Kruse died in his sleep, the victim of a probable epileptic seizure. A few days after the funeral, Vernon observed his twenty-first birthday – and a few days after that, celebrated his marriage to Miss Hazel Margaret Cutler. The newlyweds settled in with the Cutlers on Dearborn Avenue (a temporary solution, they hoped) and Vernon continued working his odd jobs. Finally, in October, he registered for Selective Service.

Things began to pick up in 1941. Vernon landed a solid six-month job at George Kamaras’ Independent Hat Shop; his work at the Illinois Central rail yard brought in a modest $25 weekly wage. It was enough to move out of Dearborn Avenue, at least.[3]

Although he was of age to serve, Vernon Kruse did not go rushing off to the nearest recruiting office when news of Pearl Harbor reached Waterloo. He must have followed the news during his long days at the railyard storeroom; perhaps his interest was piqued by stories of brave Marine aviators fighting the Japanese fleet, or perhaps he saw John Ford’s color documentary The Battle of Midway after its release in September of 1942. In late November, he quit the rail yard, put his affairs in order, and traveled to Des Moines to enlist. Kruse entered the service on 1 December 1942 and was shortly on his way to Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego – the first stop, he hoped, on the path to becoming an aircraft gunner.

He started off on the right foot. Private Kruse did well in boot camp, even earning the silver badge of a rifle sharpshooter – payoff for years of hunting – and after graduation, received orders to the Naval Air Station in Seattle, Washington. However, to his disappointment, Kruse was not there to fly. Instead, he joined the station’s Marine barracks detachment, a unit that provided base security troops, orderlies, and turned out for parades and reviews. By early 1943, it was clear that the Japanese were not planning an imminent invasion of the west coast, and duty at the Air Station quickly became routine. Kruse spent almost eight months in the damp Seattle climate; a visit from Hazel in June, and a promotion to Private First Class in July, helped to break the monotony.

In August of 1943, PFC Kruse was transferred to guard duty at Puget Sound Navy Yard – then, a short time later, received orders to report to Camp Joseph H. Pendleton in Oceanside, California. On 1 September 1943, he was formally assigned to the First Battalion, 24th Marines along with seventy-five other men. Many of the new arrivals were former drill instructors straight from Parris Island while others came from bases and depots up and down the west coast; a few had been under fire in Alaska, and Kruse traveled from Bremerton with a PFC who’d been wounded on Guadalcanal.[4] Nineteen of the new arrivals, including Vernon Kruse, were assigned to Captain Irving Schechter’s Company A.

For the next four months, PFC Kruse trained as a rifleman in one of the platoons of Company A.[5] Long hikes through the California hills, simulated battle problems, an introduction to tank tactics, and amphibious operations – including rubber boat landings – occupied his days. Kruse kept his record clean, and would have spent regular liberties in nearby San Diego with his new buddies. He may have occasionally been able to visit his mother and sisters in San Bernardino and Santa Barbara.

For the next four months, PFC Kruse trained as a rifleman in one of the platoons of Company A.[5] Long hikes through the California hills, simulated battle problems, an introduction to tank tactics, and amphibious operations – including rubber boat landings – occupied his days. Kruse kept his record clean, and would have spent regular liberties in nearby San Diego with his new buddies. He may have occasionally been able to visit his mother and sisters in San Bernardino and Santa Barbara.

On 11 January 1944, Kruse’s battalion boarded the transport USS DuPage at the San Diego docks. Two days later, they were out on the open sea, headed for an unknown destination. Rumors swirled and circulated, gaining intensity with every day that they continued westward. After a week of sailing, the Hawaiian Islands appeared, and the men stood at the rail to gaze solemnly at the wrecked battleships that still rusted in the shallow waters of Pearl Harbor. Kruse’s birthday was coming up, and he probably hope to spend it celebrating in Honolulu. Unfortunately, they spent less than twenty-four hours at Pearl – and nobody was allowed to go ashore. Vernon Kruse turned 25 aboard the DuPage instead. At least now he knew where he was headed: a pair of connected twin islands called Roi and Namur, somewhere in the central Pacific.

The battle for the islands was short and sharp. Kruse landed on Namur in the afternoon of 1 February 1944, and spent the next 24 hours fighting his way along the beach that formed the right of the Marine line. His company battled over a Japanese bunker and blockhouse complex, spent the night in captured trenches, and completed their conquest the following day. A few men from Company A were killed, and more were wounded, but PFC Kruse came through without a scratch. When he departed with his unit on 11 February, he carried along a Japanese ammo container as a souvenir of his first time under fire.

The 4th Marine Division moved into Camp Maui in the Hawaiian Islands for rest and retraining. For PFC Kruse, this involved a shift in responsibility. While he apparently demonstrated some leadership ability in combat – he was briefly classed as a squad or fire team leader – he eventually traded in his M1 Garand for a Browning Automatic Rifle, becoming a “BARman” for his squad. Although the training schedule was intense, Kruse still found time for some sightseeing, collecting a box of seashells and a souvenir scarf on his travels. He even picked up a booklet, “What To Do In Honolulu And How To Do It” – perhaps planning for a post-war vacation with Hazel at the Royal Hawaiian.[6] In May of 1944, the Division departed Maui and sailed west once again – bound, this time, for the Mariana Islands where they would participate in the invasion of Saipan.

Unfortunately, the last twenty days Vernon Kruse’s life are somewhat shrouded in mystery. He landed on Saipan on 15 June 1944, and spent most of the following three weeks in front-line combat, day or night, and occasionally both without rest. It may never be known what he did on Saipan, for no eyewitness accounts survive that mention his exploits by name. None, that is, until 5 July 1944 – his last day on earth.

On that day, PFC Davis Kruse took part in a rescue mission.

Unfortunately, it is not clear whether he volunteered for an effort to rescue a group of civilians – or whether his platoon was called up to help rescue the would-be rescuers when a Japanese machine gun opened up from a hidden position. A nasty firefight developed on that hot July afternoon, and when it ended, PFC Davis Vernon Kruse was dead – shot through the head. One of the company officers would later write that “a sniper shot [Kruse] as he was attempting to seek out and quiet a Japanese machine gun nest.”[7]

Kruse’s body was carried to safety and laid down at a collecting point. Battalion clerks confirmed his name with the identification tags he wore, and he was loaded aboard a vehicle alongside the bodies of the other ambush victims – 1Lt. Philip E. Wood, Jr., Sergeant Arthur Ervin, Technical Sergeant Arnold Richardson, and PFCs Larry Knight and Frank Hester. The following day, all six were buried in the 4th Marine Division Cemetery. Grave #830, in the fourth row of the fourth plot, was reserved for Vernon Kruse.

In 1948, the remains of Davis Vernon Kruse were returned to the United States. Hazel had remarried, but Dorothy Kruse elected to have her son’s body permanently buried in Iowa. He rests in Fairview Cemetery, Waterloo.

[1] In the 1930 census, Kreen and Dorothy were maintaining separate residences in Nobles County, Minnesota. Dorothy and seven of the children were in Lismore; Kreen was twenty miles away in Ransom working on a farm owned by Garret Toussaint and family. Interestingly, Kreen is listed on the census as “married” while Dorothy is listed as “widowed.”

[2] Although a death notice from 1944 states that Kruse attended East High, a survey in his military record lists only a grammar school education.

[3] It’s not clear where Vernon Kruse was living just before the war. He was known to be living at 312 South Barkley Street in 1942; his service records give Hazel’s address as 722 ½ Lafayette Street, and his life insurance paperwork states 2186 Lafayette Street. At some point, Hazel did return to 334 Dearborn Avenue – also occasionally given as Vernon’s legal residence. There is some indication that Vernon and Hazel lived separately; Dorothy noted that the two did not live together for more than a year before Vernon’s enlistment.

[4] PFC Harold C. MacFarland joined A/1/24 with Kruse, but was almost immediately hospitalized; he was discharged from the service by December 1943.

[5] It is not currently known which platoon Kruse was in, although the circumstances surrounding his death suggest he was in the Second Platoon under 1Lt. Roy I. Wood, Jr.

[6] This booklet was provided to guests of the Royal Hawaiian in Waikiki.

[7] The Courier-Sun, 20 May 1945.