Ross Arnold Richardson was born in Salem, Massachusetts on the tenth day of July, 1919. He grew up in Essex County (with his parents, Ross and Florence, and siblings Kendall and Barbara), attended grammar school in Peabody, and finished three years of high school before dropping out to find work. The elder Ross Richardson was a leather worker – Peabody was once “the leather capital of the world” – and probably helped his son get a job with the Morrill Leather Company. Although he never finished school, Arnold – he often went by his middle name – understood bookkeeping and shorthand, and could type at a respectable 60 words per minute. Armed with these skills, Arnold entered Morrill’s shipping department in March of 1937 – however, his employment terminated just six months later.[1]

In December of 1937, while working as a laborer, Arnold tried another career track and applied for enlistment in the United States Marine Corps. The Corps was small at the time, and joining was not as simple as walking to the station and swearing the oath. Arnold had to provide character witnesses; the Corps scrutinized his grades and made inquiries about his police record. Kendall and Florence had to sign documents agreeing to his enlistment. Collecting the paperwork took time, and Arnold did not actually enter the service until 7 April 1938. He was shipped to Parris Island for boot camp, and upon completion of his training joined the Second Battalion, 5th Marines at Quantico.

In December of 1937, while working as a laborer, Arnold tried another career track and applied for enlistment in the United States Marine Corps. The Corps was small at the time, and joining was not as simple as walking to the station and swearing the oath. Arnold had to provide character witnesses; the Corps scrutinized his grades and made inquiries about his police record. Kendall and Florence had to sign documents agreeing to his enlistment. Collecting the paperwork took time, and Arnold did not actually enter the service until 7 April 1938. He was shipped to Parris Island for boot camp, and upon completion of his training joined the Second Battalion, 5th Marines at Quantico.

While Private Richardson spent most of his first year on base at Quantico, he got a dramatic taste of overseas duty in January, 1939. His regiment participated in Fleet Landing Exercise (FLEX) 5 – the largest amphibious rehearsal that the Navy and Marine Corps could stage. While generals and admirals studied the particulars of amphibious operations with their staffs, for an enlisted Marine FLEX-5 meant boarding the USS Wyoming, a venerable old dreadnought, and sailing down to Culebra. The Marines camped in Vieques for nearly two months, and when not on duty, got to enjoy the warm weather and the unfamiliar sights and sounds of Puerto Rico. They even got to practice exotic tactics like ship-to-shore movement and landing on “hostile” shores – a first for many in the ranks. The exercise concluded in March, and the 5th Marines said a regretful goodbye to Puerto Rico before heading back to chilly Virginia.[2]

In May, Richardson was transferred from the 5th Marines to the Portsmouth Naval Prison in Kittery, Maine. This infamous facility, with its imposing, castle-like architecture and layout modeled on high-security civilian prisons – was notorious as the “Alcatraz of the East.” d housed violent or repeat offenders to Naval justice. It was rumored to be escape proof – set on an island like the real Alcatraz, surrounded by fast-flowing rivers – and guards were encouraged to shoot first and ask questions later. It was said that any guard who let a prisoner escape would be thrown into the cells to serve out the rest of the sentence – which inspired extraordinary vigilance, and not a little cruelty, on the part of the guards.[3]

Discipline was strict among the guards, as well. On 15 September 1939, Private Richardson committed the grave sin of quitting his post without being properly relieved. This wasn’t serious enough to land him in a prison cell – but he still spent ten days in solitary confinement on bread and water, and forfeited $14 from his pay in fines. Even the threat of severe punishment couldn’t restrain some men; in February of 1940, one Marine guard attacked another in a café and was booted from the service.[4] Richardson’s comparatively minor brush with discipline seems to have been enough; not long after his colleague’s trial, Richardson was promoted to Private First Class. In May, most of the guard detachment attended small-arms training in Wakefield, Massachusetts, and Richardson used the opportunity to re-qualify as a rifle sharpshooter.

Serving as a “prison chaser” was not particularly desirable duty, and Kittery was not a particularly desirable liberty town. So Richardson probably welcomed the orders transferring him to New York City in September 1940. He took up residence aboard the USS Seattle, an old armored cruiser tied up at Pier 92. Seattle was a receiving ship – essentially a floating barracks for Navy personnel in transit between duty stations or awaiting crew assignments. Guard duty was a matter of keeping order among transient sailors; Richardson might have stood a turn or two at the Seattle‘s brig, which occasionally housed prisoners bound for Portsmouth. After a few months, Richardson was transferred again – this time to the Boston Navy Yard. He spent most of 1941 standing guard over the South Boston dry docks, and probably would have run out his enlistment here – but then Pearl Harbor was attacked, and the United States was suddenly in a state of war.

Richardson stayed on at the dry docks for the first ten months of World War II, extending his enlistment period by two years, advancing in rank to corporal, and earning his expert rifleman’s badge. Not knowing where duty might take him next, he also jumped at the chance to get married to Lorraine Caroline Fuller of Lynn, Massachusetts. Little is known about their courtship, but after the wedding, Lorraine moved in with Arnold’s parents – a situation which evidently displeased Florence Richardson. She was further incensed when Arnold changed his military paperwork to name Lorraine as his next of kin and the beneficiary of his life insurance policy.

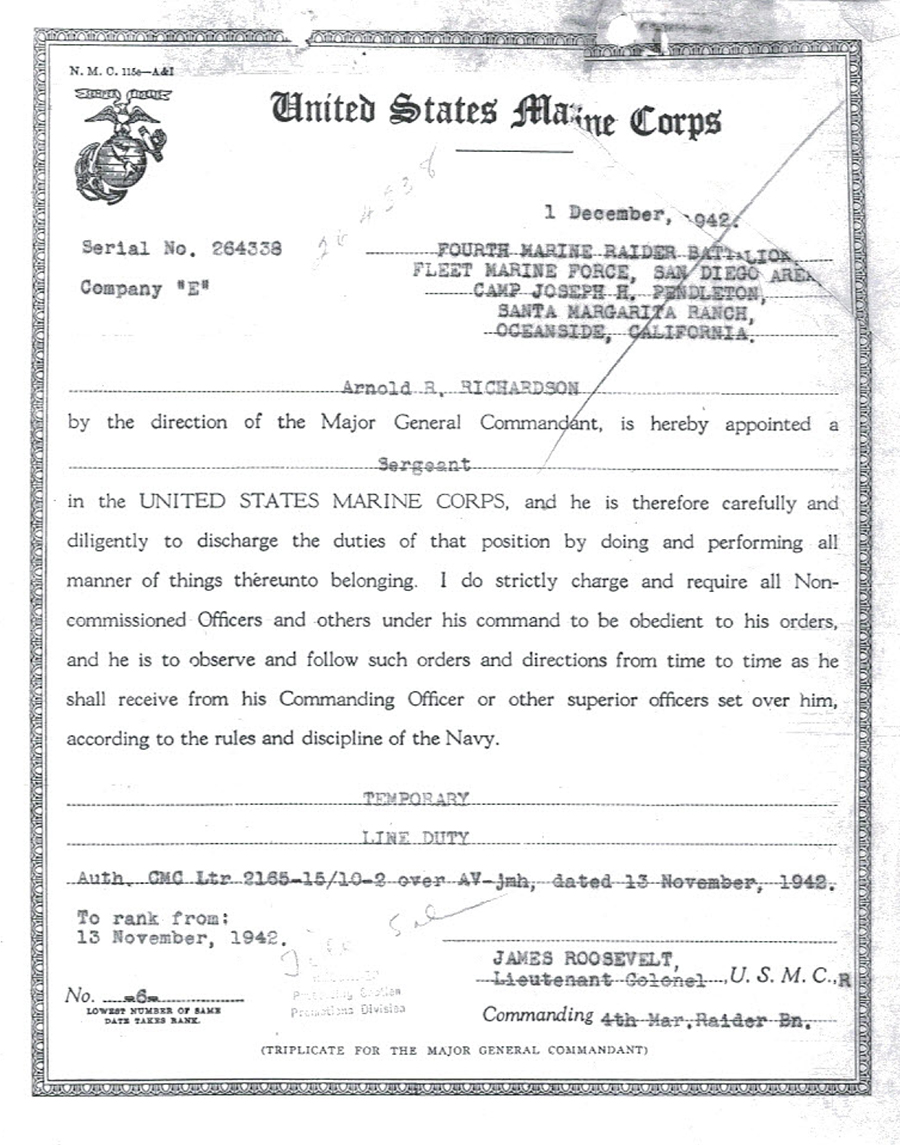

In October 1942, Richardson received another set of transfer orders which sent him all the way across the country to Camp Joseph H. Pendleton, California. He was supposed to join the camp’s maintenance detachment – and did, for a very brief period – but bailed at the earliest opportunity. Corporal Richardson wanted to become a Marine Raider, and that is exactly what he did. He volunteered for, and was accepted by, the 4th Raider Battalion which was then forming under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Roosevelt – the President’s son. Raider training was a far cry from anything Richardson had yet experienced, but he seemed to thrive under the tough regimen. In December 1942, Roosevelt promoted Richardson to the rank of sergeant.

Richardson was physically fit, individually tough, and an expert rifleman – but these traits did not set him apart in the Raiders. He did have one talent that few others possessed, however: he could type, and evidently had a knack for administration. Days after his promotion, Richardson was transferred to the Raiders’ Company F to assume the role of acting First Sergeant – the senior personnel and administrative NCO for almost two hundred men. A man of more senior rank soon transferred in and Richardson was relegated to the role of company clerk, but in that brief time he had proved his abilities.

This very proficiency would ultimately spell the end of Richardson’s Raider career. In early 1943, he was sent to First Sergeant’s School at Camp Pendleton – an eight-week course in administration – while the 4th Raider Battalion set sail for overseas duty. While Richardson did well on his course, he regretted being left behind, and when interviewed for permanent assignment preferences in April 1943 requested duty with the Fleet Marine Force or another Raider unit. He got his wish – the following month, he was assigned to Headquarters Company, First Battalion, 24th Marines. The battalion’s previous “topkick” had just received a commission, so Sergeant Richardson stepped in to fill his shoes.

The First Sergeant’s role was primarily personnel and administration, as well as overseeing the myriad clerical needs of several hundred men. Richardson inherited a group of subordinates who had already worked together for months, and the man he replaced, Warrant Officer Gerald V. Casey, was now the company commander. Thus supported, Richardson carried out his duties for the entire summer and most of the fall of 1943 as the battalion gradually built up its strength and proficiency in the training areas of Camp Pendleton. In November, he lost his “acting” role to a more senior NCO and became the battalion’s chief clerk; his reward for months of extra work was a promotion to the rank of staff sergeant.

The First Sergeant’s role was primarily personnel and administration, as well as overseeing the myriad clerical needs of several hundred men. Richardson inherited a group of subordinates who had already worked together for months, and the man he replaced, Warrant Officer Gerald V. Casey, was now the company commander. Thus supported, Richardson carried out his duties for the entire summer and most of the fall of 1943 as the battalion gradually built up its strength and proficiency in the training areas of Camp Pendleton. In November, he lost his “acting” role to a more senior NCO and became the battalion’s chief clerk; his reward for months of extra work was a promotion to the rank of staff sergeant.

When the 4th Marine Division departed Camp Pendleton in January of 1944, many clerks and administrators were told to stay behind. This rear echelon watched the combat troops depart with individual mixtures of regret and relief. (They would soon depart on a mission of their own, sailing for the Hawaiian Islands to help establish a new camp.) A few were deemed necessary for the upcoming operation, and Staff Sergeant Richardson – the expert rifleman with Raider training – was not about to be left behind again. After issuing any necessary instructions to his clerical staff, he boarded the USS DuPage at San Diego and sailed out into the Pacific on 13 January 1944.

Three weeks later, he was a combat veteran. While there are no surviving eyewitness accounts to tell the story of Arnold Richardson’s experiences in the battle of Roi-Namur, it is known that several men from battalion HQ – who would normally have stayed behind the front lines – went out looking for action. This aggression came at a cost: one of his colleagues, Platoon Sergeant James Adams, and the battalion commander, Lt. Colonel Aquilla J. Dyess, were killed in the attack. Whether Richardson followed suit or stuck to his duties is not known – either way, he survived without injury and departed from the islands on 11 February.

Richardson’s star continued to rise after the battalion arrived at Camp Maui. On 4 April 1944, he was promoted to Technical Sergeant; three days later, he extended his enlistment for another two years. Finally, on 28 April, Richardson was transferred from the clerks to Company A, where he once again assumed the role of acting First Sergeant. He earned the respect of the company commander, Captain Irving Schechter, and was generally regarded as “a nice guy” by the men in his charge.[5]

The final testament to Arnold Richardson’s character may be found in documents generated by his death.

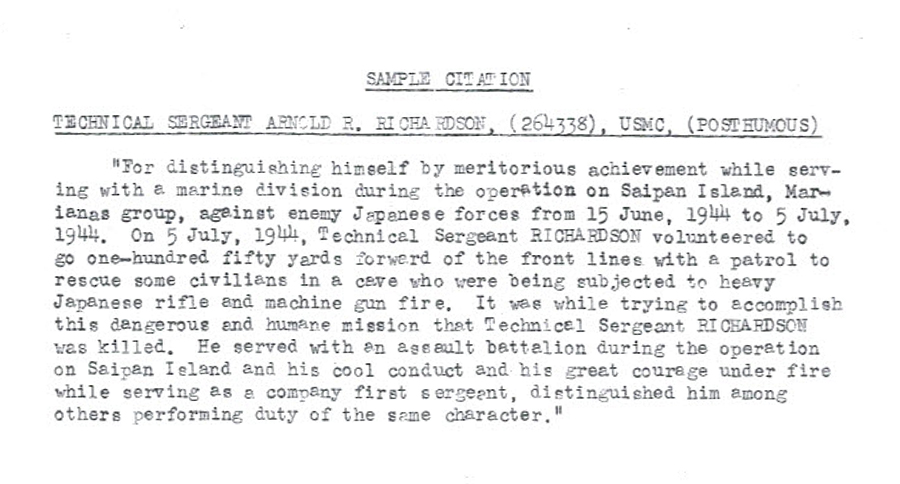

He landed on the island of Saipan on 15 June 1944, and during nineteen days of battle “his cool conduct and his great courage under fire while serving as a company first sergeant distinguished him among others performing duty of the same caliber.”[6] On the twentieth day, 5 July 1944, he was at his post with company headquarters when a group of civilians was spotted scurrying for American lines. All firing ceased, and when 1Lt. Philip E. Wood, Jr. asked permission to take a patrol to rescue the refugees, Richardson immediately volunteered to go along. Wood, Richardson, Sergeant Arthur Ervin, a Navy corpsman, and a handful of others – between eight and twelve – gathered their gear and passed through their company front lines.

The civilians had come from a cave nearly 200 yards away, and the patrol made its way cautiously forward, with the lieutenant in the lead. They were anticipating an ambush – and, with the sudden crack of a Japanese rifle, Lieutenant Wood was down, shot through the abdomen. Sergeant Ervin went racing out after the lieutenant, with the corpsman right on his heels; a machine gun opened up and both would-be rescuers were hit. Richardson attempted to provide some covering fire – but exposed himself just a fraction too much. A flying piece of metal, either a bullet or a shell fragment, struck him in the head. Death was almost instantaneous.

Within a few minutes, the company’s Second Platoon was on the scene. In the short but bloody firefight that followed, several more Marines were hit, but the Japanese ambushers were driven off or killed. It was too late for Richardson, Lieutenant Wood, Sergeant Ervin, and PFCs Frank Hester, Davis Kruse, and Lawrence Knight. The six Marines were buried in the 4th Marine Division cemetery the following day. Two of them – Wood and Richardson – would receive posthumous Bronze Star medals for their roles in the patrol.[7]

News of Arnold’s death soon reached 202 Main Street, Peabody. The shock triggered “a physical and mental breakdown” for Lorraine Richardson, and she was unable to work. Florence, whose antipathy towards Lorraine was now exacerbated by grief, took out her feelings on her daughter-in-law. “Everything seems to come to the wife who has been living with us,” she complained to her congressman. “I wonder if you can look into this matter as everyone concerned feels that the father and mother of that boy shouldn’t be left out of this all together…. He was a very dear boy to us, and it is not an easy thing to realize that he is gone.”[8] By September, Lorraine had vacated 202 Main Street and was back with her own family in Lynn. Her husband’s death had turned her world upside down.

News of Arnold’s death soon reached 202 Main Street, Peabody. The shock triggered “a physical and mental breakdown” for Lorraine Richardson, and she was unable to work. Florence, whose antipathy towards Lorraine was now exacerbated by grief, took out her feelings on her daughter-in-law. “Everything seems to come to the wife who has been living with us,” she complained to her congressman. “I wonder if you can look into this matter as everyone concerned feels that the father and mother of that boy shouldn’t be left out of this all together…. He was a very dear boy to us, and it is not an easy thing to realize that he is gone.”[8] By September, Lorraine had vacated 202 Main Street and was back with her own family in Lynn. Her husband’s death had turned her world upside down.

In the end, Lorraine decided she would take Arnold’s place. She enlisted in the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve in October 1944, and served for nearly two years in the paymaster’s office in Washington, D.C. The work helped her come to terms with her loss, as did the few of Arnold’s personal effects she received from overseas. In September of 1945, Private First Class Lorraine Richardson accepted the Bronze Star Medal on behalf of the late Technical Sergeant Arnold Richardson.

Lorraine eventually overcame her grief. In 1946, she married Army veteran John J. Shaw, moved to Connecticut, and started a family. She passed away in March, 2018.

Florence Richardson regained her status as Arnold’s primary next of kin following Lorraine’s remarriage. In 1948, she elected to have her son’s remains returned to his native Massachusetts. Today, he is buried in Middleton’s Oakdale Cemetery.

[1] Arnold Ross Richardson, Official Military Personnel File.

[2] Ibid.

[3] This was not official policy, but made an effective threat nonetheless.

[4] “Marine Stabbed In Scuffle At Cafe,” The Portsmouth Herald (7 February 1940).

[5] Robert Johnston, interview by the author, 2015.

[6] Arnold Richardson, sample Bronze Star citation, in Official Military Personnel File

[7] Richardson’s final citation also cited his proven abilities as a company first sergeant over the course of the battle.

[8] Richardson Official Military Personnel File

Enjoyed reading ! If you can find anything about Dino Dominic Caiazzi I would sure love the info, I’m his daughter and have found out he was in 3 battles one of them being Iwo Jima .

Thank you, Kathleen Caiazzi-Kulp

Sent from my iPhone

>