| NAME: Lawrence Elmer Knight |

NICKNAME: Larry |

SERVICE NUMBER: 815009 |

|||||

| HOME OF RECORD: Heth, AR |

NEXT OF KIN: Mother, Mrs. Pearlie M. Knight |

||||||

| DATE OF BIRTH: 4/19/1923 |

SERVICE DATES: 2/17/1943 – 7/5/1944 |

DATE OF DEATH: 7/5/1944 |

|||||

| CAMPAIGN | UNIT | MOS | RATE | RESULT | |||

| Roi-Namur | A/1/24 | 745 | PFC | WIA | |||

| Saipan | A/1/24 | 746 | PFC | KIA | |||

| INDIVIDUAL DECORATIONS: Purple Heart with Gold Star |

LAST KNOWN RANK: Private First Class |

||||||

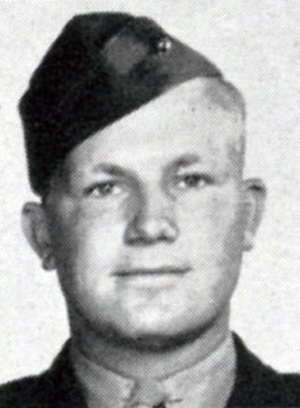

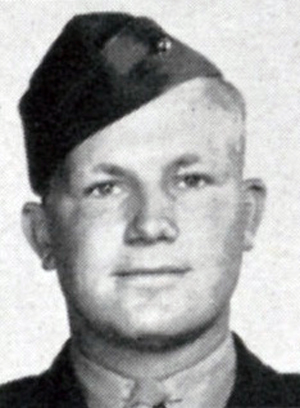

Lawrence Elmer Knight was born in the small city of Parkin, Arkansas on 19 April 1923. He spent most of his childhood in the communities of Parkin, where he attended school, and Tyronza, where his father Elmer farmed cotton. As the oldest boy, Larry learned how to help out around the farm – his mother, Pearlie, had her hands full with a family that eventually counted seven children – and became adept at driving and repairing the family tractor and trucks. He also found time for hobbies and extra curriculars. School offered woodworking and machine ship classes; Larry also played baseball and football, and was an avid swimmer. An aspiring shutterbug, he even learned to mix his own chemicals and make his own prints.[1]

Lawrence Elmer Knight was born in the small city of Parkin, Arkansas on 19 April 1923. He spent most of his childhood in the communities of Parkin, where he attended school, and Tyronza, where his father Elmer farmed cotton. As the oldest boy, Larry learned how to help out around the farm – his mother, Pearlie, had her hands full with a family that eventually counted seven children – and became adept at driving and repairing the family tractor and trucks. He also found time for hobbies and extra curriculars. School offered woodworking and machine ship classes; Larry also played baseball and football, and was an avid swimmer. An aspiring shutterbug, he even learned to mix his own chemicals and make his own prints.[1]

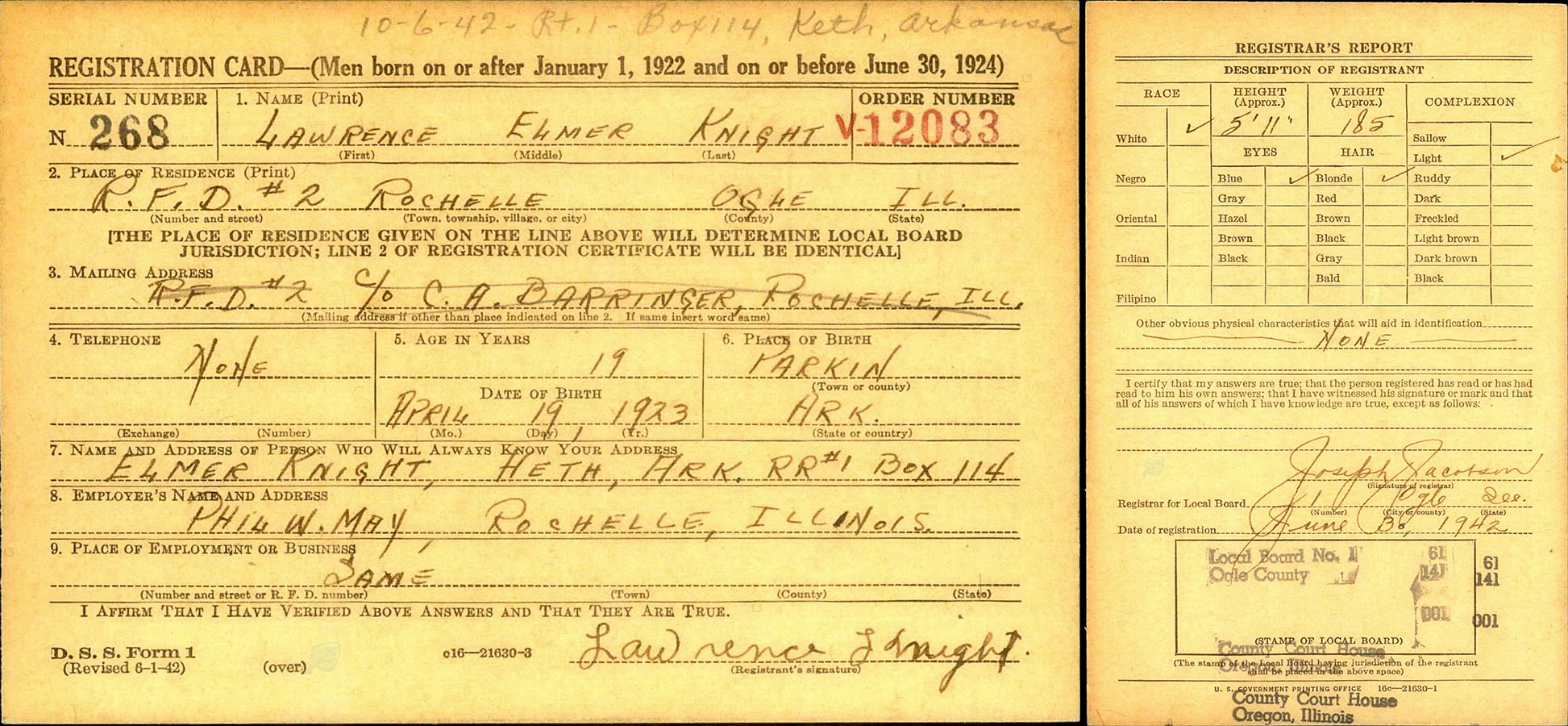

Larry left school in 1940, after completing his sophomore year at Parkin High. He joined the Civilian Conservation Corps, and during his six-month stint attained the level of “assistant leader” of a trucking group. This experience was quickly parlayed into employment, and Larry was hired by the California Produce Company to drive a stake bed truck on a regular delivery route between Rochelle, Illinois and Chicago. At the age of eighteen, he was able to earn his own living, and moved to Rochelle in 1941. News of the Pearl Harbor attack reached him there, and in June of 1942 he registered with the draft board of Ogle County.

In the fall of 1942, Larry Knight evidently returned to Arkansas. His family had moved to an even smaller community, Heth, in St. Francis County. That November, he was summoned for a physical examination, found fit to serve in the armed forces – and then sent home to wait. Thanksgiving passed, then Christmas, then the New Year. News reports carried stories of Marines fighting on Guadalcanal, soldiers battling in North Africa, and the Navy operating in both theaters at once. When his orders finally arrived on 17 February 1943, Knight packed a bag and traveled more than a hundred miles to Little Rock to be sworn in to the United States Marine Corps. In short order, he was on his way to Recruit Depot San Diego.

After a few weeks of boot camp, an interviewing NCO questioned Larry about his background and where he wanted to serve. Larry wasn’t sure – motor transport sounded good, but then so did the exciting life of a parachutist. He was open to the Fleet Marine Force, but preferred tanks if possible – anything to do with driving. The NCO thought for a moment, then marked down his recommendation: “Auto Equipper.” And so, after completing boot camp, Private Knight was sent to Motor Transport School.[2]

Unfortunately, the assignment that sounded perfect on paper was a poor fit in reality. After three weeks, Private Knight was dropped from the Motor Vehicle Operators course as “unqualified” and sent over to Camp Elliott for infantry training. He was bound for the FMF after all. Although the post was definitely not his first choice, Knight was not exactly a fish out of water at infantry school. He was well-built – at five feet ten, he weighed 180 pounds at induction and probably added more muscle at boot camp – and well-suited to a rugged life. Plus, he was skilled with a rifle: in boot camp, he qualified as a sharpshooter, missing the coveted “Expert” rating by less than ten points. Knight’s stay at Training Camp Elliott would be extended due to some illness or accident that landed him in the hospital for six weeks, but he finally completed the coursework and emerged as a qualified rifleman.[3]

On 26 August 1943, more than 140 young Marines, most with just a few months in the service, were shipped down from Camp Elliott to Camp Joseph H. Pendleton. There, they were informed that they would be joining the newly-designated First Battalion, 24th Marines. An NCO read off a list of names – Frank Hester, Lawrence Pantlin, John Rayley, Tommy Lynchard, Lawrence Knight, and 43 more – and directed them to the barracks of Company A, commanded by Captain Irving Schechter. From there, they were assigned to smaller and smaller units – platoons, squads, and fire teams.

Larry Knight quickly got to know his new comrades in the Second Platoon. He took orders from the lieutenant, a genteel South Carolinian named Roy I. Wood, Jr., and direction from the platoon sergeant, a former DI named Parker McBride. He trained and palled around with the other privates and PFCs of the platoon – Rigdon, Manson, Larson, Loutzenhiser, Jones – and became friends with Tommy Lynchard, a Mississippi farm boy also fresh out of training.[4] The company trained hard during the fall and winter of 1943; Knight learned to operate a Browning Automatic Rifle, and even attended a specialized assault tactics school in December. For his efforts was made a Private First Class effective 1 January 1944. Just two weeks later, he boarded the transport USS DuPage and sailed out into the unknown.

Larry Knight quickly got to know his new comrades in the Second Platoon. He took orders from the lieutenant, a genteel South Carolinian named Roy I. Wood, Jr., and direction from the platoon sergeant, a former DI named Parker McBride. He trained and palled around with the other privates and PFCs of the platoon – Rigdon, Manson, Larson, Loutzenhiser, Jones – and became friends with Tommy Lynchard, a Mississippi farm boy also fresh out of training.[4] The company trained hard during the fall and winter of 1943; Knight learned to operate a Browning Automatic Rifle, and even attended a specialized assault tactics school in December. For his efforts was made a Private First Class effective 1 January 1944. Just two weeks later, he boarded the transport USS DuPage and sailed out into the unknown.

A Western Union Telegram arrived for Pearlie Knight on 28 February 1944. The first few words – “DEEPLY REGRET TO INFORM YOU” – were enough to terrify any parent. Gathering her fortitude, Pearlie read on. Lawrence had been wounded – still worrisome, but at least he was alive – and no further details were immediately available. By this date, the Knights had probably heard of the battle of Roi-Namur on the radio or in the paper; if so, they knew the 4th Marine Division was responsible for the conquest, and assumed that Larry was somehow involved.

Unbeknownst to them, Larry Knight had quite an active time in his first battle. His company landed on the afternoon of 1 February 1944, and started moving along the beach to take up positions on the right flank of the Marine line. At first, they only saw the occasional dead Japanese soldier, but as they approached Nadine Point they started taking small-arms fire, and after that everything was a confused jumble of shooting, running, taking cover, and surviving the mayhem. The action culminated in a wild charge, twelve Marines pursuing 75 Japanese, and ended – for Knight – with a bullet in the face that creased his nose and grazed his lip. The difference between life and death was a fraction of an inch, but Knight didn’t want to leave; an officer had to order him to the rear, where he passed the night getting bandaged and listening to the continuing firefight along the front lines. A medical team evacuated him in the morning, and within a few days he was at a hospital in Hawaii.

I am writing about your son, PFC Lawrence E. Knight, who was wounded while serving under my command in Namur Island. My purpose in writing you is three-fold.

One, to tell you, you should be proud of your son, he was in the fight all the time and when wounded had to be ordered to leave, his spirit was such that although wounded, he wanted to stay with the platoon.

Second, was to assure you his life was not in danger and that he will receive the best of care.

Thirdly, I mean this more than you know. If at any time I or any of our company officers can be on any assistance, what so ever to you or your son, please feel free to call on us.

– Roy Wood, letter dated 26 February 1944[5]

Knight’s memories of his first battle survive in his own words, told to correspondents who flocked to the hospital to get the scoop on the fight for the Marshall Islands. Although shot in the mouth, and reticent at times, the young Marine opened up about the battle – and his experiences were printed in papers across the country.

“I didn’t do anything more than anyone else did. All the men seemed happy to go into action. This was my first time in action, but I’ll say the guys in my gang did a swell job.”[6]

“The first Jap I saw was an officer, cornered in a hole with a bunch of his men. He ran out. We got ready to search him. Then he ran back and started to grab a knife. I shot him.”[7]

“Private Lawrence Knight, 20, of Parkin, Ark., told how a Marine corporal, whose helmet was shot off, got mad for the first time, dashed into a trench, killed the two Japs who did it, and retrieved the helmet.”[8]

“There was a Jap, lying very still. Hoppie was firing his rifle over the edge of the hole. The Jap beside him was playing possum. While Hoppie was aiming at a sniper, the Jap tried to sneak behind him and put a knife in him. Hoppie just whirled around and let the Jap have the bayonet in the ribs. Then he swung around and kept right on fighting. I was right there when a bullet got him. It was too bad about Hoppie. He was a real man.”[9]

Knight’s wounds, while dramatic, proved to be superficial and he rejoined his company on 24 March 1943. Also returning on that date was Corporal Arthur Ervin, whom Knight recognized from the helmet incident. Just one month later, in a ceremony at Camp Maui, Knight watched as Ervin received the Navy Cross for his heroic exploits on Roi-Namur. Much of the rest of the time at Maui was spent in training – absorbing the lessons of the previous battle, and preparing for the intricacies of the next. Several new men were absorbed into the company – replacements for those permanently lost in action – and Knight’s status as both a combat veteran and recipient of a Purple Heart (a rarity in his company at that time) probably gave him an air of authority to the untested Marines.

In May of 1944, the 4th Marine Division boarded transports and sailed from Maui for the invasion of Saipan. From the moment they landed on 15 June, the Second Platoon was in the thick of the fighting. Many years after the war, Tommy Lynchard jotted down some fragmented memories – which, one can only imagine, his friend Larry Knight would have shared if he survived.

We went through thick woods early one morning. Just at day light, I peeped through some very thick cover and spotted a cave. Japs were asleep in the entrance. We threw grenades and fired our weapons into their heads. I was within 12 feet of four or five… I opened up with my BAR and sprayed them all. We moved out before the smoke cleared.

Once I held my squad leader’s head up while the Corpsman tried to doctor his gunshot wound. He was hit hard through the back. Blood was gushing out all over. I got sick at my stomach.

One morning our Captain passed the word down the line to move out in 5 minutes. It was just getting daylight…. Japs were everywhere in the cane fields. Some had rifles, some only had bayonets, some had [demolition] charges, some blew themselves up. We really had a field day as we caught them in the open. At least 100 or more tried to cross a dry stream bed. It was like shooting ducks in a barrel… our boys cut them down before any of them ever reached safety. It was a BARman’s dream come true.

Our closeness to each other seemed better when the chips were down. When we could retrieve our dead, we would, but at times we could not.

This experience as a farm boy was by far the greatest experience of my life. It was a rough and rugged, almost like a nightmare. We had to have a desire to want to live so very bad to make it – and, of course, God’s help.[10]

A BARman and his buddy on Saipan’s Kagman Peninsula, 26 June 1944. NARA.

Knight endured nineteen days of this chaos. On the twentieth – 5 July 1944 – he was up early, as his battalion made a circuitous march around a neighboring Army unit to get into position for yet another attack. The Second Platoon found its assigned place in line and hit the deck, grabbing a smoke of a few moments of rest while awaiting the word to attack. The company’s mortar section was firing rounds over their heads, adding their 60mm bombs to the opening bombardment. Everything was going according to plan – and then the mortars ceased fire. Word trickled back that a group of civilians was trying to reach the safety of Marine lines, and the mortar section leader – 1Lt. Philip E. Wood, Jr. – and his assistant, Sergeant Arthur Ervin, were taking a patrol to rescue them. Knight might have even seen the exhausted, frightened civilians traipsing to the rear for medical treatment.

Within minutes, Company A heard the telltale rattle of a Japanese machine gun and the answering pops of American weapons. Corpsmen and stretcher bearers began running towards the spot where the patrol left the lines. And then the company’s executive officer, “Big Harry” Reynolds, arrived, yelling at Roy Wood to get the Second Platoon up and moving. There had been an ambush, and they were the rescue party. Tommy Lynchard hefted his BAR and moved out on the double. When he reached the ambush point, a firefight was already in progress, and several men were lying dead and wounded on the ground.

Enraged, Lynch charged into some nearby woods with his BAR, shooting up every Japanese soldier he came across. Out of ammunition and alone, he realized the danger and scooted back to the company. As Captain Schechter organized a flanking mission to break the ambush, corpsmen worked furiously on the casualties. Many men were wounded – including Pantlin and Rayley, who joined Company A on the same day as Lynchard and Knight – and six were dead.

Lynch was horrified to see his buddy on the ground. “He was shot right through the head,” he later recalled. “He wasn’t quite dead – he was lying there making a sound like he was blubbering – but you could tell he was going to die.”[11]

Sadly, Tommy Lynchard’s prediction came true. Lawrence Elmer Knight died on Saipan at the age of twenty-one.

When the firing stopped, Lynch moved up to check out the cave that had been the patrol’s objective. Inside, he found some sixty civilians – men, women, and children, some wounded, all terrified. According to Tommy Lynchard, every one of the civilians was brought to safety.[12] Larry Knight’s last patrol had accomplished its mission.

Larry was a good Marine, in camp and in combat, well liked by all, capable of doing any job well. As you know he was in my platoon on Namur and rejoined us after he got out of the hospital. I know there is nothing I can say that will lessen your sorrow, but I want to tell you how he met his death. Our company was in the attack on the 5th of July. We had sent out a platoon which had been ambushed by the enemy. It was during our attempt to get to these men that Lawrence was killed. He gave his life in an effort to help his buddies.

– Roy Wood, letter dated 10 August 1944[13]

The following day, Larry Knight was buried in Grave 831 of the 4th Marine Division Cemetery, alongside Lieutenant Wood, Sergeant Ervin, Technical Sergeant Arnold R. Richardson, PFC Davis V. Kruse, and PFC Frank R. Hester. His only personal belongings – a ring and a fountain pen – were shipped home to Pearlie Knight.

In 1948, the remains of Lawrence Elmer Knight were returned to the United States. Pearlie originally requested that he stay on Saipan, but eventually agreed to burial in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific.

[1] Lawrence Elmer Knight, Official Military Personnel File.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Tommy Lynchard, telephone interview with the author, 2014.

[5] Letter transcribed for Cross County Bank, 2001. Archived webpage.

[6] Roy Cummings, “U.S. Marines Charge Onto Namur Singing Marine Hymn and Joking,” The Honolulu Star-Bulletin (14 February 1944).

[7] “‘Great Time’ Bared By Chillicothe Marine Who Shot Down Japs,” The Cincinnati Enquirer (14 February 1944).

[8] “Wounded Yanks ‘Just Did A Job’ On Namur Isle,” The Chicago Tribune (14 February 1944).

[9] “Hopkins Slew Jap Before Losing Life,” The Philadelphia Inquirer (15 February 1944). The incident with the Japanese soldier was witnessed by other members of the company. However, the re-telling implies that Hopkins was killed shortly thereafter. In fact, several hours elapsed. Knight was not “right there” but in the vicinity, having just been wounded himself.

[10] Tommy Lynchard, unpublished manuscript. Author’s collection.

[11] Lynchard telephone interview

[12] Ibid.

[13] Letter transcribed for Cross County Bank, 2001. Archived webpage.